Overview

Commodity exposures as part of a multi-asset portfolio provide several investment benefits:

- Cyclical commodities (energy and industrial metals) offer positive exposure to growth.

- Cyclical commodities and gold also offer protection against inflation.

- Low correlation to other asset classes provides additional diversification.

However, commodity investing within an ESG framework presents several challenges. Chief among them is the need to mitigate their environmental impact in the fight against climate change.

Some investors have used commodity-related equities (stock investment in producers) as a proxy for commodity exposure. Indeed, single equities are easier to invest in, especially when factoring ESG criteria. However, this is only a partial solution and fails to capture much of the value that commodities can add to a multi-asset portfolio.

Investing directly in commodities using an ESG-investing framework raises its own challenges even when focusing solely on their environmental impact. The social and environmental cost of consumption and production is not embedded in market prices. Carbon emissions are therefore externalities that need to be addressed. This can be achieved primarily in three ways: global tax, green markets or carbon offsetting.

In this article, we start by discussing why we think that direct commodity exposure is the best approach to benefit from the investment outcomes associated with the asset class. We then highlight the existing channels in which ESG concerns around commodity investing are being addressed globally. Finally, we focus on most investors’ preferred channel – participation in an emissions trading scheme – and the various methods they can use to integrate carbon emissions trades into their portfolios.

Commodities vs Commodity-related Equities

Commodity-related equities are often used as a proxy for commodity exposure. Single stocks appear less exotic than commodity investments. They can be accessed on an unlevered basis and they don’t bear the risk of physical delivery. In addition, they are less complex from regulatory and ESG perspectives. For example, in Europe, UCITS regulation makes direct commodity investments more complex to achieve: investors must contend with the physical delivery risk associated with commodity futures and commodity benchmark diversification rules, among others. ESG assessment for equities has been the subject of many debates, but there is some common ground, while commodity markets have been largely ignored as we will show later.

However, commodity-related equities are an imperfect proxy for commodity investment:

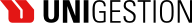

- They provide a different exposure to macro regimes compared to direct commodity investing. Indeed, an analysis of respective Sharpe ratios over the past two decades reveals that they expose investors primarily to growth regimes while offering virtually no exposure to inflation-driven regimes.

Figure 1: Sharpe Ratios During Macro Regimes

Source: Bloomberg, Unigestion; 01/1999-04/2021; Commodity-related Equities: MSCI ACWI Commodity Producers; Commodities: BCOM TR Index.

Commodity-related equities are an imperfect proxy for commodity investment.

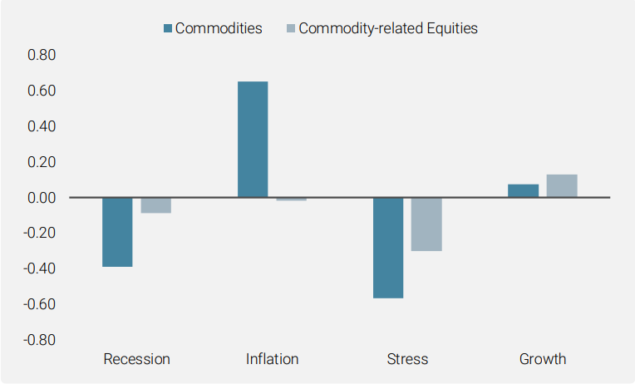

- They provide a negative asymmetry of capture to direct commodity investment, but behave like a leveraged exposure to equities. Indeed, commodity-related equities have a beta to commodities of more than 1 during down months and notably below 1 during positive months. At the same time, their beta to global equities is always at or above 1.

Figure 2: Monthly Beta of Commodity-related Equities

Source: Bloomberg; 01/1999-04/2021; Commodity-related Equities: MSCI ACWI Commodity Producers; Global Equities: MSCI ACWI NTR Index, Commodities: BCOM TR Index.

We strongly believe in the benefits of diversifying a portfolio of assets across key macroeconomic regimes. To that end, the identification of macro regimes and the sensitivity of each risk premia to the regime is key. As commodity-related equities have not historically provided the same level of inflation regime sensitivity as direct commodities, we do not deem them a suitable replacement.

Commodity-related equities have not historically provided the same level of inflation regime sensitivity as direct commodities.

At Unigestion, we believe that integrating ESG criteria into our investment processes is essential to better managing the risks associated with our investments. Increasingly, governments are penalising non-sustainable behaviour (carbon tax, company bans on social issues) and investors are integrating ESG criteria in their thought processes. This heightened attention will have a long-term impact on the underlying asset class. This is reflected in our approach which favours direct investment in commodities.

Commodity Investing and ESG

Reporting on ESG factors for commodity and commodity-related companies is complex to such a degree that one can see it as the poster child for ESG concerns:

- Production and consumption often result in a greater environmental footprint than other human activities, be it through greenhouse gas (GhG) emissions, water pollution or other externalities.

- Production has often been associated with poor social standards such as working conditions in mines.

- Multiple jurisdictions can lead to significant governance issues. Commodity producers tend to have production (drilling or mining) sites, processing plants and commercialisation in different countries with variable quality of governance. In particular, production sites are often located in countries with a poor history of governance.

Standardisation efforts are made at the corporate level through various reporting initiatives such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). It is complex yet possible at the company level (a key challenge is assigning relative weights to different factors) and even more complex at industry level (assigning relative weights of power consumption across sectors such as mining or refining). The level of operational complexity of rating E, S and G factors increases further when it comes to the actual commodity.

Assessing the environmental impact of commodity investments is a first step and a part of it can be addressed in a quantifiable manner through the reduction of CO2 or other GhG emissions (emissions hereafter).

Reduction of emissions can be enforced in three primary ways:

- One can tax emissions.

- One can constrain it through “green markets”.

- One can offset it through carbon credit.

Global Tax

As presented in a 2020 paper by Goldman Sachs1, a globally coordinated taxation of emissions would be a very efficient tool to reduce emissions, especially if accompanied by green subsidies.

A global taxation scheme for emissions would rely on a global agreement between world governments on:

-

- the assessment of standard emission levels across industries;

- a fixed cost per ton of GhG, and

- a global tax and subsidy system.

Such an approach would be an optimal solution in theory. It is targeted and addresses the issue globally (and climate change is global). It creates a known cost for emissions and its implementation is simple. However, in practice, it creates a risk of overpaying through the inaccurate assessment of these costs. It could also lead to negative outcomes: if profits can be increased by producing (thus polluting) more, tax becomes an additional marginal cost that might be insufficient to rein in emissions. In addition, it is politically unrealistic in the real world. While global agreement on social cost and its value could be reached, it would require a globally coordinated policy shift and the opposing interests of emitting countries and those negatively affected by emissions render such a solution politically hard to envision.

Green commodity markets are still in their infancy and face several hurdles.

Green Markets

This bottom-up approach addresses the issue in two distinct ways:

- The ESG score of producers is similar to the ESG score for equities. The output of a “green” producer would be green commodities.

- For physical commodities, it would rely on the division of the universe based on production techniques that would result in clean (green) or dirty commodities. The same company could then produce clean and dirty commodities depending on their production line as long as its output is clearly separated. Eg: London Metal Exchange ‘green aluminium’, London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) Good Delivery gold bullion.

However, green commodity markets are still in their infancy. Indeed, green markets face several hurdles that have yet to be tackled.

The setup of green markets is expensive to put in place. Emissions assessment can be complex. Scope 1 (Direct emissions from activities) and Scope 2 (Indirect emissions associated with the purchase of energy such as electricity, heating or cooling) are straightforward, Scope 3 (All other indirect emissions from activities of the organisation, from sources that it does not own or control2) is not. Determining what a “green commodity” is becomes an exercise in assessing the minimum criteria for each commodity and applying them producer-by-producer across countries. This monitoring is expensive.

The LBMA sets acceptable delivery standards for gold.

In addition, a green commodity will only represent a sub-set of a specific commodity. It involves a large amount of tracking not available for all commodities, but it can be achieved, as in the case of Good Delivery bullion. In this case, the LBMA sets acceptable delivery standards for gold and silver bullion in the London market, including requirements regarding responsible sourcing3. Another example is the tentative launch of LME green aluminium. ESG alternatives would represent a small portion of these markets, at least initially, and would likely encounter liquidity concerns very quickly, in particular for smaller commodity markets.

Carbon Offsetting

Carbon offsetting systems are market-based. Emitters buy tons of carbon equivalent to the carbon footprint resulting from their economic activities. The supply and demand balance of carbon emissions therefore determines the cost of polluting. There are two different kinds of market-based systems:

Baseline-and-credit Mechanisms

In such systems, emitters that reduce their emissions or compensate for them with sustainable projects receive carbon credits (Certified Emission Reductions & Verified Emission Reductions or VER), which they can monetise. These projects follow three main axes: forestry (primarily reforestation as a way to sequester carbon), renewable energies and energy efficiency initiatives in developing countries. The key point of these projects is that they are voluntary. This way a company can compensate for its residual emissions, but there is no requirement of doing so. The main advantage of this approach is that VER certificates pay for past performance. A certificate is only issued when the carbon avoidance has been already achieved (and certified).

The EU ETS is the largest allowance trading system in the world and its effectiveness has made it a blueprint for others.

Emission Trading Schemes (ETS, Cap-and-Trade)

This is not a new concept. Schemes have existed since the early 2000s with pre-emptive legislation pre-dating this. In ETS, regulators set an upper limit on emissions that are then traded freely according to industry benchmarks, or auctioned. These allowances must be surrendered by emitters at a future date. ETS act as a mechanism to limit the total allowable emissions.

Details vary by scheme, but they are based on the same broad principles:

- Limit the number of covered GhG emissions for regulated sectors

- Equalise the marginal cost of emissions reduction for all its entities

- Set a price signal for operators through the cap on emissions

They require strong governance and create the potential for insufficient reduction, but they offer clear and transparent rules. They also create a defined outcome for the system (the number of allowances is a known quantity) and allow for market pricing. These schemes are supported by the Paris agreement.

In essence, ETS create a marketplace for emissions allowances. The EU ETS is the largest allowance trading system in the world and, after several phases of trial and error, its effectiveness has made it a blueprint for others.

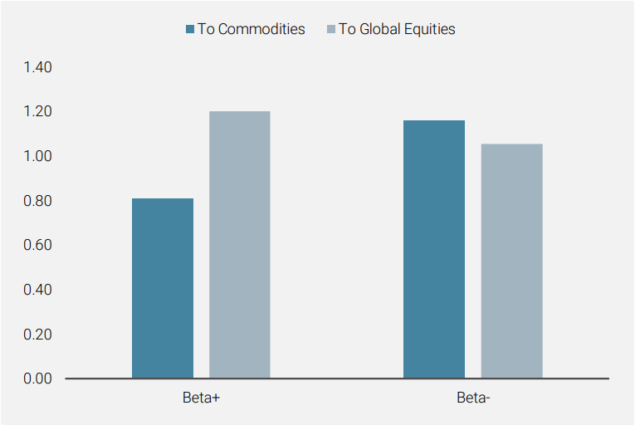

In 2021, 29 carbon pricing initiatives were implemented or scheduled for implementation for a total of 8.73 GtCO2e, representing 16.1% of global GhG emissions.

Figure 3: Summary Map of Regional, National and Subnational Carbon Pricing Initiatives

Source: WorldBank. https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/map_data

The framework provided by ETS creates a regulated market structure which in turn makes traded allowance the most efficient tool to integrate ESG criteria into commodity investing. In particular, EU Allowances (EUA) future contracts trade like normal futures on ICE and are very easily accessible. They also have the best liquidity and market depth among existing ETS futures.

EU Allowances (EUA) future contracts trade like normal futures on ICE and have the best liquidity and market depth.

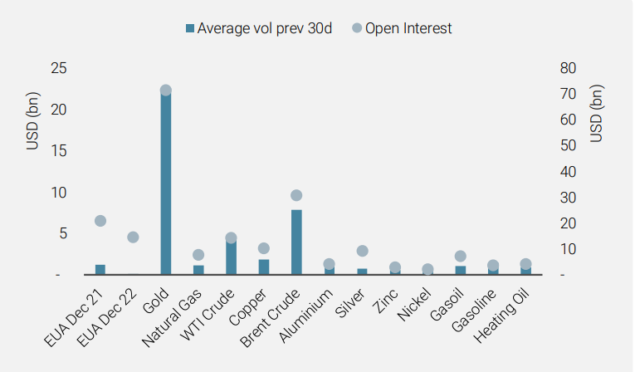

Figure 4: Average 30-Day Trading Volume and Open Interest of EUA and BCOM Underlying Commodities (ex-Agriculture and Livestock)

Source: Bloomberg, including EUA futures and BCOM ex-Agriculture and Livestock underlying single commodity futures. As of 20.08.2021

ETS and Commodities

ETS are focused on commodity consumers such as power generators, heavy industry and aviation, but carbon price reintroduces externalities into the system. Indeed, as the price of carbon increases, so does the incentive to find alternative energy sources such as renewables and more efficient ways of producing refined products.

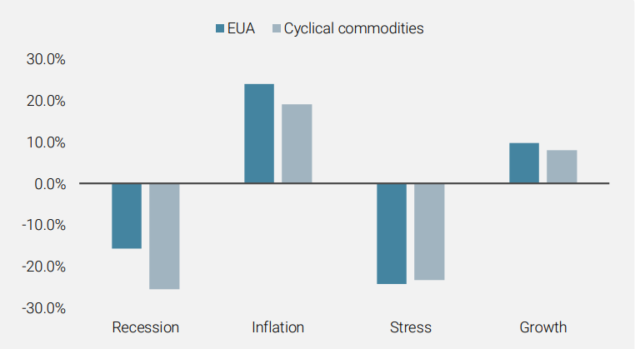

Carbon allowances (represented in Figure 5 by EUA) share similar investment characteristics as direct commodity investments, behaving as both an inflation hedge and a growth asset.

Figure 5: Regime-conditional Returns in Excess of Full Sample Average

Source: Bloomberg; EUA – 05/2005-04/2021, includes the phase 1 period (2005-2007) that saw prices collapsing on bad calibration of the supply of EUA; Cyclical commodities – 02/1977-04/2021

Institutional investors are increasingly participating in ETS for two main reasons: 1) to offset the carbon impact of their other investments as part of a sustainable investment strategy; 2) in response to expectations of a sharp price increase4. For this next section, due to much more favourable liquidity conditions, we will focus on EUA futures as an implementable solution should an investor choose to adopt this route. However, investors should also be cognisant that due to potential regulatory influence, EUA prices can be prone to significant idiosyncratic risk (as seen in 2006-2007). Additionally, the EUA market remains relatively small at around USD 300 billion versus USD 40 trillion in global equities. Data is also less available relative to other asset classes, with its futures having only started trading in 2005.

Carbon allowances share similar investment characteristics as direct commodity investments.

Introducing Carbon Contracts in an Asset Allocation

There are three main ways an asset allocator can incorporate EUA futures in their portfolio. We highlight the key pros and cons below.

1) Include EUA futures as an overlay with an allocation that offsets the carbon footprint from commodity exposures

Pros: It explicitly offsets investors’ carbon footprint arising from commodity exposure and does not require a long historical sample to calibrate allocation. Carbon offsetting is an increasing ESG investment requirement and a common solution adopted by investors.

Cons: Computing the carbon footprint arising from commodity exposure is a complex and data-intensive process. There is currently no industry standard on how to measure the footprint for each commodity. The availability of data can also be a hurdle in some cases. This computation can be outsourced to brokers but investors would need to trust their methodology and the quality of their data. Furthermore, there are no explicit financial objectives associated with such an allocation.

2) Include EUA futures in a strategic allocation, treating EUA as a standalone risk premium

Pros: Increasing investor appetite over the past decade has driven demand for EUA to levels that exceed supply and this surplus demand is expected to continue into the foreseeable future. This should provide support for its prices. As such, it can be argued that this has created a new risk premium with positive expected return. By incorporating EUA as a standalone risk premium in one’s strategic allocation, investors will only require the historical time series of EUA prices and should implicitly account for return and risk characteristics as part of the process.

Increasing investor appetite over the past decade has driven demand for EUA, which is expected to continue.

Cons: Carbon emissions related to one’s commodity exposure would not normally be a factor in deciding an asset’s strategic allocation. As such, the carbon offset generated from a strategic allocation to EUA may or may not fully offset the carbon emissions associated with one’s commodity exposure. In addition, the reliability of EUA futures as a return stream is questionable as it can be subject to significant regulatory intervention. The incorporation of a new asset into a strategic allocation often requires historical data (e.g. historical volatility, sensitivity to key macroeconomic regimes). The reliable history of EUA futures is relatively short as bank indices’ only started tracking the front December month (the most liquid contract) in 2012.

3) Include EUA futures in a strategic allocation, incorporating EUA as part of a cyclical commodities strategic allocation

Pros: EUA have similar macroeconomic regime sensitivities to cyclical commodities. They tend to perform well in inflationary and growth regimes. In addition, from a carbon offset perspective, it would make sense to allocate more to EUA futures should one allocate more to cyclical commodities as they tend to be the heavier carbon emitters in the commodity complex. As opposed to incorporating EUA as a standalone risk premium, incorporating EUA in a “cyclical commodities” strategic allocation would likely lead to a lower allocation to EUA. This would alleviate some of the concerns around unreliable and/or relatively short historical data.

Cons: Similar to 2) above

While each approach has its own merits and challenges, as an asset allocator, our strategic portfolio aims to harvest a diversified set of risk premia. Specifically, in determining a strategic allocation, we would consider each risk premia’s sensitivities to key macroeconomic regimes, and the frequency of occurrence of such regimes. Due to the relatively short history of EUA futures, a lower return reliability due to potential regulatory invention and a similar macroeconomic regime sensitivity to cyclical commodities, our preferred methodology would be incorporating EUA as part of a “cyclical commodities” strategic allocation. We recognise that this does not necessarily fully offset the carbon footprint of an investor’s overall commodity allocation and might not meet the requirements of investors aiming for carbon neutrality.

Carbon trading makes an appealing solution for investors that want to gain commodity exposure in a responsible way.

For specific sustainability requirements, we would implement carbon offsetting solutions for the full footprint of the commodity asset class. We could even consider extending the offset to cover the full portfolio.

Conclusion

Carbon emissions allowances are not the definitive answer to integrate ESG considerations into commodity investing, but we believe this is the most suitable solution today. They make an appealing solution for investors that want to gain commodity exposure in a way that fully exploits the asset class’s investment characteristics, including inflation sensitivity, but in a responsible way. Carbon futures markets are more liquid and this liquidity is growing. In addition, regulators around the world appear supportive of these instruments as a privileged mechanism to combat climate change. We believe that adding EUA to an asset allocation toolkit is a key element of ESG integration in commodity investing.

Bibliography

- Global Economics Analyst: Mitigating Climate Change via Taxes and Subsidies (Goldman Sachs, October, 2020)

- Commodities Comment Metals Investing & ESG: Transparency the Best Policy (Macquarie, January, 2021).

- http://www.lbma.org.uk/good-delivery-rules

- Commodity Insights: Towards a Carbon-Neutral Commodity Index (Goldman Sachs, October 2020)

- Carbon Primer (Morgan Stanley, November, 2017)

- EU Emissions Trading System: A Primer to the EU ETS (UBS, January, 2021)

- World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/

1Mitigating Climate Change via Taxes and Subsidies, Goldman Sachs, October 2020

2These emissions, from activities such as business travel, procurement, waste and water, usually account for the greatest share of a producer’s carbon footprint.

3http://www.lbma.org.uk/good-delivery-rules

4IMF estimates a carbon emission price of $75/ton to achieve the Paris Agreement target while scientific journal Nature estimates a price of $77-124/ton to achieve ‘net zero’ by 2030.

Important Information

Past performance is no guide to the future, the value of investments, and the income from them change frequently, may fall as well as rise, there is no guarantee that your initial investment will be returned. This document has been prepared for your information only and must not be distributed, published, reproduced or disclosed by recipients to any other person. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation.

This is a promotional statement of our investment philosophy and services only in relation to the subject matter of this presentation. It constitutes neither investment advice nor recommendation. This document represents no offer, solicitation or suggestion of suitability to subscribe in the investment vehicles to which it refers. Any such offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to purchase shall be made only by formal offering documents, which include, among others, a confidential offering memorandum, limited partnership agreement (if applicable), investment management agreement (if applicable), operating agreement (if applicable), and related subscription documents (if applicable). Please contact your professional adviser/consultant before making an investment decision.

Where possible we aim to disclose the material risks pertinent to this document, and as such these should be noted on the individual document pages. The views expressed in this document do not purport to be a complete description of the securities, markets and developments referred to in it. Reference to specific securities should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell. Unigestion maintains the right to delete or modify information without prior notice. Unigestion has the ability in its sole discretion to change the strategies described herein.

Investors shall conduct their own analysis of the risks (including any legal, regulatory, tax or other consequences) associated with an investment and should seek independent professional advice. Some of the investment strategies described or alluded to herein may be construed as high risk and not readily realisable investments, which may experience substantial and sudden losses including total loss of investment. These are not suitable for all types of investors.

To the extent that this report contains statements about the future, such statements are forward-looking and subject to a number of risks and uncertainties, including, but not limited to, the impact of competitive products, market acceptance risks and other risks. Actual results could differ materially from those in the forward-looking statements. As such, forward looking statements should not be relied upon for future returns. Targeted returns reflect subjective determinations by Unigestion based on a variety of factors, including, among others, internal modeling, investment strategy, prior performance of similar products (if any), volatility measures, risk tolerance and market conditions. Targeted returns are not intended to be actual performance and should not be relied upon as an indication of actual or future performance.

No separate verification has been made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information herein. Data and graphical information herein are for information only and may have been derived from third party sources. Unigestion takes reasonable steps to verify, but does not guarantee, the accuracy and completeness of information from third party sources. As a result, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made by Unigestion in this respect and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. It should only be considered current as of the date of publication without regard to the date on which you may access the information. Rates of exchange may cause the value of investments to go up or down. An investment with Unigestion, like all investments, contains risks, including total loss for the investor.

Legal Entities Disseminating This Document

UNITED KINGDOM

This material is disseminated in the United Kingdom by Unigestion (UK) Ltd., which is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (« FCA »). This information is intended only for professional clients and eligible counterparties, as defined in MiFID directive and has therefore not been adapted to retail clients.

UNITED STATES

This material is disseminated in the U.S. by Unigestion (UK) Ltd., which is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). This information is intended only for institutional clients and qualified purchasers as defined by the SEC and has therefore not been adapted to retail clients.

EUROPEAN UNION

This material is disseminated in the European Union by Unigestion Asset Management (France) SA which is authorized and regulated by the French “Autorité des Marchés Financiers” (« AMF »).

This information is intended only for professional clients and eligible counterparties, as defined in the MiFID directive and has therefore not been adapted to retail clients.

CANADA

This material is disseminated in Canada by Unigestion Asset Management (Canada) Inc. which is registered as a portfolio manager and/or exempt market dealer in nine provinces across Canada and also as an investment fund manager in Ontario, Quebec and Newfoundland & Labrador. Its principal regulator is the Ontario Securities Commission (« OSC »). This material may also be distributed by Unigestion SA which has an international advisor exemption in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Ontario. Unigestion SA’s assets are situated outside of Canada and, as such, there may be difficulty enforcing legal rights against it.

SWITZERLAND

This material is disseminated in Switzerland by Unigestion SA which is authorized and regulated by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (« FINMA »).

Document issued September 2021.