The Role of Fossil Fuels in the Climate Transition

Head of Fundamental Research, Equities

ESG Analyst, Equities

Key Points

- Despite the recent push into renewables, our energy mix is still dominated by fossil fuels.

- Falling investment in oil & gas production has increased the risk of supply shocks.

- The energy transition is inflationary by nature.

Overview

Despite all the measures announced over the past decades to combat climate change, the recent supply shock from the war in Ukraine is a timely reminder to what extent we are still dependent on fossil fuels. While energy efficiency, renewables, fuel switching and carbon capture embody the solutions on the path to decarbonisation, the supply and management of fossil fuels such as oil, gas and nuclear will be key to ensure an orderly energy transition.

Energy is the Backbone of Our Economy

For centuries, economic growth was anaemic while population growth was slow. Fossil fuels were first used around 100–200 AD for heating and cooking, but the turning point came much later with the industrial revolution. Indeed, everything changed in the 18th century when Newcomen and Watt invented the steam engine. Suddenly, machines started to do the work previously done by humans and animals. Oil was first used in the 19th century, and in the 1950s, the world’s first nuclear power station was built.

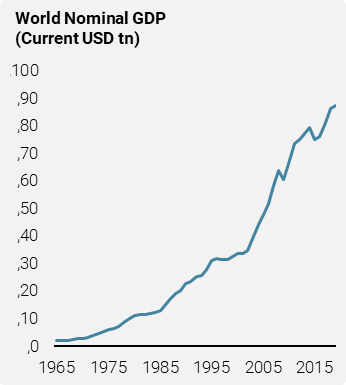

With more energy came more machines in order to produce and transport goods as well as food. Our economy is therefore essentially outputs by machines that use energy. The two charts below illustrate the high correlation between annual economic growth and annual consumption of primary energy sources.

Figure 1: Correlation Between Economic Growth and Consumption

Source: Smil, BP. Data as at 2019.

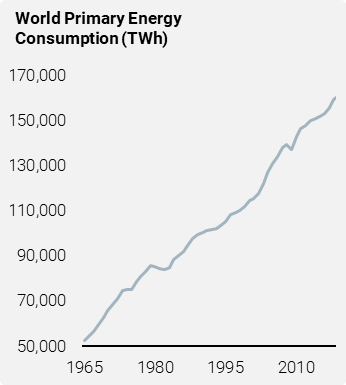

Fossil Fuels Remain the Bulk of Our Primary Energy Sources

Humans started to use renewable energy, such as wind to sail boats or activate windmills to grind grain, well before using fossil fuels. However, these sources of energy are dispersed and fluctuate greatly in intensity over time. For decades, when environmental and climate impact were of little concern, fossil fuels offered much higher energy density and reliability, as they could be stored and used when needed. Without surprise, and despite the recent push into renewables, our energy mix is still dominated by fossil fuels.

Figure 2: World Direct Primary Energy Consumption Mix by Decade

Source: Smil, BP. Data as at 2019.

Defining the Energy Transition

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that in order to stay within the global warming 1.5˚C target, the world has a maximum budget of 2,600–2,900 GtCO2 of anthropogenic emissions, of which 2,200 has already been used. With current emissions at approximately 42 GtCO2 a year, the remaining budget will be depleted in 10–17 years if nothing is done. To put this into perspective, with less than a third left of our total emissions budget and a current population approximatively three times greater, future generations have about 10% of the emissions budget per capita than their ancestors.

« Energy-related emissions count for approximately 73% of global GHG emissions, the majority of which are CO2 emissions. »

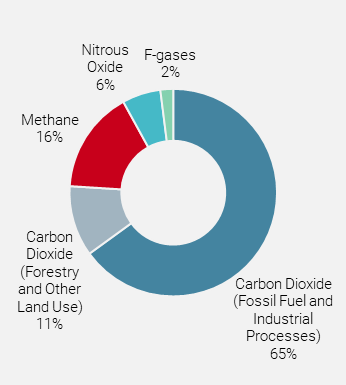

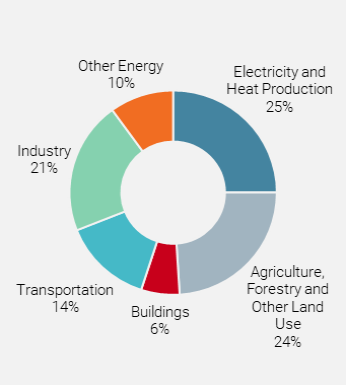

The energy transition is the passage of the global energy sector from fossil-based to zero-carbon by the second half of this century. At its heart is the need to reduce energy-related CO2 emissions to limit climate change. Energy-related emissions count for approximately 73% of global GHG emissions, the majority of which are CO2 emissions.

Figure 3A: Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Gas

Figure 3B: Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Economic Sector

Source: IPCC. Data as at 2014.

« Renewable energy and energy efficiency measures can potentially achieve two thirds of the required carbon reductions, but this will take decades. »

When analysing CO2 emissions, the focus is typically on power generation and personal vehicles. Power generation is responsible for >35% of total energy CO2 emissions, while light road vehicles represent only 6–8%. A successful energy transition needs to include solutions for the remaining energy-related CO2 emissions. For these so-called ‘hard to abate’ sectors, such as heavy trucking, iron and steel, cement, shipping and aviation, scalable solutions are still being developed.

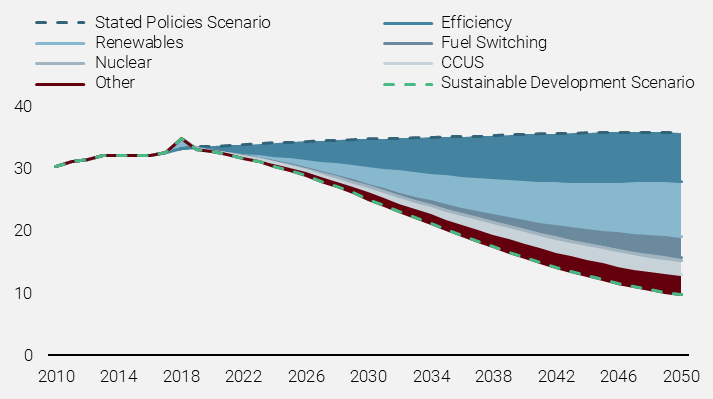

In total, renewable energy and energy efficiency measures can potentially achieve two-thirds of the required carbon reductions, but this will take decades.

Figure 4: CO2 Emissions Reductions by Measure in the Sustainable Development Scenario Relative to the Stated Policies Scenario, 2010–2050

Source: International Energy Agency (IEA). Data as at 2019.

Efficiency – The Low Hanging Solution

Among all the primary energy used, only one-third is converted into useful energy. The remaining two-thirds are lost, due to inefficiencies in electricity generation, transport, heavy industry, and buildings. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), energy efficiency is one of the best solutions for an inclusive, sustainable, affordable and secure energy system.

Overall, energy efficiency has been improving at a yearly rate of 2.3% from

2011–2016, but only by 1.3% during the past five years, as the trend slowed with very little progress in 2020 due to Covid-19. However, in the IEA scenario, we need at least a yearly 4% energy efficiency gain, more than double the current pace.

Buildings are an obvious choice for better energy efficiency, their electricity and heating being responsible for 19% of global emissions and 39% when including construction materials and works. However, such improvement is hampered by the pace of renovation works, notably due to the availability of labour in regions like Europe.

Renewables – A Long Way to Go

Switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar for power generation or from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles, are well-known examples of decarbonisation solutions. However, wind and solar energy still only represent a small amount of the energy mix, are erratic energy sources and need energy storage solutions and/or back-ups from manageable energy sources such as hydro, nuclear, gas, or even coal.

Others – Fuel Switching and Carbon Capture and Storage

Fuel switching is replacing high-sulphur fuels with low-sulphur alternatives. For electricity production, it can be replacing high-sulphur coal by low-sulphur coal or natural gas. For transportation, it can be replacing traditional fuels (gasoline, diesel) by renewable fuels such as renewable diesel. Renewable hydrocarbon biofuels offer engine compatibility, increased energy security, and fewer emissions than conventional fuels. However, availability of raw materials for renewable fuel is limited.

At times, increased energy efficiency or alternative low-carbon energy sources may not be viable, for example, heavy industries in the short to medium-term. In these cases, carbon capture and storage (CCS) facilities or nature-based solutions, such as reforestation, can play an important role.

Supply of Fossil Fuels is Key to a Smooth Energy Transition

For the global energy sector, a 25–30% reduction in emissions is needed by 2030 to stay below the 2°C trajectory and 50% for a 1.5°C trajectory. According to the IEA, demand-side efficiency improvements represent around 40% of the total emissions abatement opportunity needed to deliver the Paris Agreement goals, particularly in the near term.

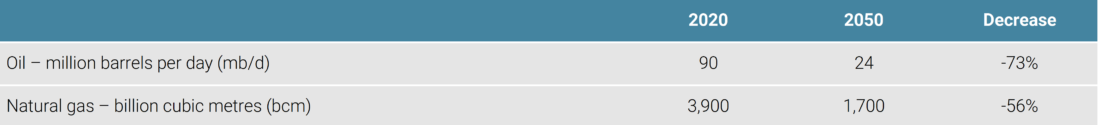

Fossil fuel exploration needs to stop in the IEA’s Net Zero Emission (NZE) scenario, i.e. no new oil and natural gas fields beyond those that have already been approved for development. However, this does not mean zero investments and developments anytime soon, as existing infrastructures need maintenance and approved projects still need to be developed and implemented in order to meet the growing energy demand.

Figure 5: Production Under the NZE Scenario by the IEA

Source: IEA. Data as at 2019.

Coal – The Most Urgent

« Coal is the highest emitting and polluting fossil fuel. Its use must decline first and foremost to prevent runaway climate change. «

Coal is the highest emitting and polluting fossil fuel. Its use must decline first and foremost to prevent runaway climate change. This requires a rapid phase out of coal use in power generation as well as reductions in industrial processes. While most developed countries have moved away from coal (although the current energy crisis is sparking restarts), developing countries are still heavily reliant on this energy source, still representing more than 25% of total primary energy used.

However, in addition to the cost of switching away from coal, some countries may be reluctant as their domestic resources represent security of supply. For China, the largest global emitter, coal is the only primary energy source for which it is self-sufficient, currently accounting for more than 60% of its energy mix. This is particularly important for China, whose energy needs continue to grow, while geopolitical tensions between east and west remain elevated, as does the price of imported energy.

At Unigestion, we strongly support the energy transition and therefore we exclude any companies having more than 10% of revenues from coal. For our Article 9 strategies (products targeting sustainable investments), revenue from coal must not exceed 1% or the company has to have a publicly available disposal plan.

Oil – Managing the Supply Decline

Oil plays a central role throughout the global economy, from transport to plastics, and its use must significantly decline over the coming decades to reach decarbonisation goals. The IEA expects oil demand to fall from around 90 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2020 to 24 mb/d in 2050, a 73% decrease.

However, we have yet to reach the peak in demand and even when that peak is reached, oil will continue to be used for decades. 2020 marked a nine-year low for global demand at 91mb/d due to Covid-19, but the IEA expects demand to rise above 104 mb/d by 2026 as economies fully reopen. This would be an all-time high.

While we wait for demand to peak, several forces may limit the availability of future supply. Firstly, the price of oil suffered from two large demand shocks during the China slowdown in 2014/15 and the pandemic in 2020. These demand shocks made energy groups more cautious in their investments. Second, short-term spare capacity remains tight, as some regions have passed their production peak (Europe and Norway peak production was in 2000, source: BP) or have limited capacity to expand (Middle East). Third, as the energy transition rhetoric gathers pace, governments and shareholders increasingly pressure energy groups to switch away from oil and gas production. As a result, investments have fallen significantly, increasing the risk of supply shocks.

Unigestion doesn’t have an exclusion per se on oil companies, but our core strategies, with their defensive profile, tend to naturally have little exposure to this sector which is cyclical by nature. Our Article 9 strategy only considers energy companies with a clear path toward transition.

Gas – East and West Competing for the Same Supply

It is difficult to find other sources of gas, while all large economies look to secure their own supply in a sector that has been underinvested in recent years.

Gas plays an important role in electricity, heating and industry in the transition to a net-zero emissions world. However, gas remains a non-renewable emitting source of energy and the IEA expects natural gas demand to fall from 3,900 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2020 to around 1,700 bcm in 2050. Nonetheless, in the short/medium-term, gas is the fastest growing fossil fuel, as overall energy demand continues to grow and gas becomes an alternative to coal.

Against this backdrop and due to the war in Ukraine, Europe wants to cut its gas dependency from Russia by two-thirds in 2022 and fully within five years. There are two challenges to this. First, it is difficult to find other sources of gas, while all large economies look to secure their own supply in a sector that has been underinvested in recent years. The other challenge is the infrastructure, as gas is less fungible than oil and needs to be transported either via pipelines or in the form of liquid natural gas. This solution requires gasification units in Europe and a more interconnected domestic pipeline network.

In the case of gas, Unigestion has no specific restrictions but, regarding our Article 9 strategy, only electricity generation under certain conditions would comply with the EU taxonomy.

Nuclear – Will Remain Small but Required

With around two-thirds of the world’s electricity coming from burning fossil fuels, reaching climate goals by 2050 will require at least 80% of it to be shifted to low carbon sources, according to the IEA. Generating electricity in a low carbon world requires low emission electricity generation and the ability to cope with the fluctuating nature of sources such as wind and solar. Despite significant drawbacks, such as accident risk and long-term waste storage, reaching NZE goals without nuclear power is even more difficult, as it has two major advantages: it has very low emissions and is a reliable base load source of energy.

Unigestion doesn’t have any constraints on nuclear. For our Article 9 strategy, as for gas, only the activity of generating electricity using nuclear fuel is aligned with the EU taxonomy.

Fossil Fuels as a Back-up Power for Renewables

Before energy storage capacity becomes widely available and abundant, back-up generation is needed to supply the residual load when wind, solar, storage and reservoir hydro dispatches are not enough. Renewable Energy Sources (RES) plants typically operate with capacity factors ranging from 30–80% for hydro, 20–40% for wind farms and 10–20% for photovoltaic. The residual load can typically be provided by gas, nuclear or even coal power plants.

Energy Storage

Energy storage is another critical element to achieve net zero by 2050. In 2020, total battery storage capacities were 17GW, helped by a record 5GW addition in China that year. According to the IEA scenario, the world needs 150GW of battery storage capacity in 2030 and 600GW in 2050. This capacity is critical to address the hourtohour variability of wind and solar.

Hydrogen has a role to play as it can be used to store energy. However, due to its poor efficiency through the value chain, hydrogen requires vast amounts of renewable energy, which we don’t yet have.

Energy Transition: Inflationary and Resource Intensive

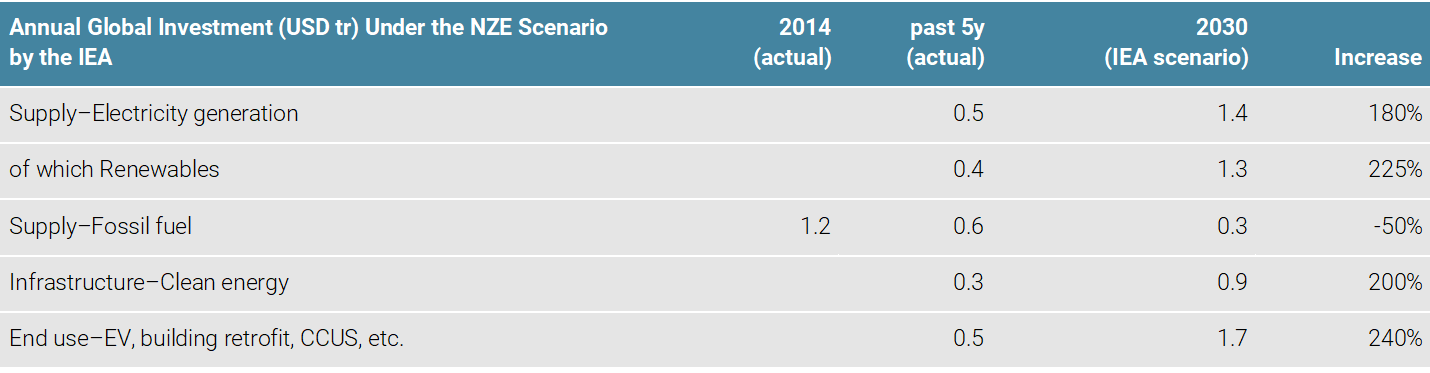

The energy transition is inflationary by nature. Machines using dense and reliable energy sources (fossil fuels) are being replaced by new ones that require a lot of metal to build and rely on diffuse and erratic sources such as wind and solar, which make the system more complex. As shown in the table below, according to the IEA, we roughly need to double the annual rate of investments in areas such as electricity generation, clean energy infrastructure, etc. to reduce emissions.

Figure 6: Annual Global Investment (USD tr) Under the NZE Scenario by the IEA

Source: IEA. Data as at 2019.

These figures assume that we can source all critical minerals needed to manufacture these new machines, as solar photovoltaic plants, wind farms and electric vehicles generally require more minerals to build than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. For example, a typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car, and an onshore wind plant nine times more than a gas-fired plant. As a result, since 2010, the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50%, reflecting the share of renewables in new investments.

Conclusion

First and foremost, as our economic growth remains tied to the availability of more energy, our consumption of primary sources of energy continues to grow. This include demand for fossil fuels.

The developed world and Asia are short of fossil fuels such as oil and gas. We are thus competing with each other to ensure sufficient supply while the energy transition is slowly happening and the balkanisation of the world is ongoing. Due to the war in Ukraine, Europe is finding the task of diversifying its supply of gas away from Russia very hard.

Energy prices act as a tax on consumers and therefore on the entire domestic economy. In Europe, more than half of the retail fuel price is tax-based, while the other half is a “tax” imposed by oil producing countries. Only the former can be used to finance the domestic energy transition. It is therefore key that the gasoline price paid at the pump reflects a high domestic tax (the price of carbon) to finance investments and discourage consumption, rather than an expensive commodity (crude oil) that acts as a pure cost.

The two recent oil shocks, coupled with governments and shareholders increasingly applying ‘green’ pressure on energy groups, have significantly diminished their spending, increasing the risk of a supply shock. As such, in the medium-term, it is of utmost importance to keep the supply of oil and gas sufficient to ensure the price of these commodities remains low. This will allow more spending by governments and the private sector in favour of the energy transition.

Important information

Past performance is no guide to the future, the value of investments, and the income from them change frequently, may fall as well as rise, there is no guarantee that your initial investment will be returned. This document has been prepared for your information only and must not be distributed, published, reproduced or disclosed by recipients to any other person. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. This is a promotional statement of our investment philosophy and services only in relation to the subject matter of this presentation. It constitutes neither investment advice nor recommendation. This document represents no offer, solicitation or suggestion of suitability to subscribe in the investment vehicles to which it refers. Any such offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to purchase shall be made only by formal offering documents, which include, among others, a confidential offering memorandum, limited partnership agreement (if applicable), investment management agreement (if applicable), operating agreement (if applicable), and related subscription documents (if applicable). Please contact your professional adviser/consultant before making an investment decision.

Where possible we aim to disclose the material risks pertinent to this document, and as such these should be noted on the individual document pages. The views expressed in this document do not purport to be a complete description of the securities, markets and developments referred to in it. Reference to specific securities should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell. Investors shall conduct their own analysis of the risks (including any legal, regulatory, tax or other consequences) associated with an investment and should seek independent professional advice. Some of the investment strategies described or alluded to herein may be construed as high risk and not readily realisable investments, which may experience substantial and sudden losses including total loss of investment. These are not suitable for all types of investors.

To the extent that this report contains statements about the future, such statements are forward-looking and subject to a number of risks and uncertainties, including, but not limited to, the impact of competitive products, market acceptance risks and other risks. Actual results could differ materially from those in the forward-looking statements. As such, forward looking statements should not be relied upon for future returns. Targeted returns reflect subjective determinations by Unigestion based on a variety of factors, including, among others, internal modeling, investment strategy, prior performance of similar products (if any), volatility measures, risk tolerance and market conditions. Targeted returns are not intended to be actual performance and should not be relied upon as an indication of actual or future performance.

Data and graphical information herein are for information only and may have been derived from third party sources. Unigestion takes reasonable steps to verify, but does not guarantee, the accuracy and completeness of this information. As a result, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made by Unigestion in this respect and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. It should only be considered current as of the date of publication without regard to the date on which you may access the information. Rates of exchange may cause the value of investments to go up or down. An investment with Unigestion, like all investments, contains risks, including total loss for the investor.

Backtested or simulated performance: Backtested or simulated performance is not an indicator of future actual results. The results reflect performance of a strategy not currently offered to any investor and do not represent returns that any investor actually attained. Backtested results are calculated by the retroactive application of a model constructed on the basis of historical data and based on assumptions integral to the model which may or may not be testable and are subject to losses.

Changes in these assumptions may have a material impact on the backtested returns presented. Certain assumptions have been made for modeling purposes and are unlikely to be realized. No representations and warranties are made as to the reasonableness of the assumptions. This information is provided for illustrative purposes only. Backtested performance is developed with the benefit of hindsight and has inherent limitations. Specifically, backtested results do not reflect actual trading or the effect of material economic and market factors on the decision-making process. Since trades have not actually been executed, results may have under-or over-compensated for the impact, if any, of certain market factors, such as lack of liquidity, and may not reflect the impact that certain economic or market factors may have had on the decision-making process. Further, backtesting allows the security selection methodology to be adjusted until past returns are maximized. Actual performance may differ significantly from backtested performance.

Unigestion SA is authorised and regulated by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). Unigestion (UK) Ltd. is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and is registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Unigestion Asset Management (France) S.A. is authorised and regulated by the French “Autorité des Marchés Financiers” (AMF). Unigestion Asset Management (Canada) Inc., with offices in Toronto and Montreal, is registered as a portfolio manager and/or exempt market dealer in nine provinces across Canada and also as an investment fund manager in Ontario and Quebec. Its principal regulator is the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC). Unigestion Asset Management (Copenhagen) is co-regulated by the “Autorité des Marchés Financiers” (AMF) and the “Danish Financial Supervisory Authority” (DFSA). Unigestion Asset Management (Düsseldorf) SA is co-regulated by the “Autorité des Marchés Financiers” (AMF) and the “Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht” (BAFIN).

Document issued in September 2022.