Trade war is probably not highest on the list of concerns for many market participants, but it remains a significant threat to both the world economy and to markets. Fewer boats are getting bought: freight indices have been decreasing significantly recently and even more so since the start of the year with the first application of the trade talks. It means both the end of an era dominated by a liberal ideology and increased uncertainty given retaliation risks. When thinking of the longer run, it is one of our key risks. A clear correlation exists between the acceleration in wealth growth that took place during the second industrial revolution and the evolution of transportation. The acceleration of the speed at which people and goods could be transported has had a significant impact on our mental representation of space itself: what used to seem prohibitively distant is now a day’s journey. World trade fed on this significant evolution and lead to a growth acceleration, a notion put forward by the tenants of the “New Economic History” by Nobel prize winners, D. North and R. Fogel. The invention of the steam machine made economist David Ricardo’s dream a reality. Across the two centuries that followed, most countries intensified their specialisation, actively trading what they had an edge for against what others would have to offer, forming the foundation of world trade as we know it, and supported by the then dominant liberal ideology. Throughout the 20th century, economic growth and world trade growth have walked hand-in-hand, for better and for worse. The better first: in line with economic theory, developed economies that pursued this path of specialisation managed to first operate a transition from an industry-intensive economy with low productivity to a service-based economy with impressive productivity gains. The latter entails higher wages which in turns promotes higher national wealth. Some emerging countries also managed to make this transition, following the post-war Japanese model of producing cheaper goods than those produced elsewhere until it became a major industrial nation. This ended for Japan in the 90s, but for others, the “Asian dragons” as they were called in 2000, the music is still on. The worse: this intensification of the economic connection between countries has had a tendency to lead the major economies to export, willingly or unwillingly, their slowdowns and recessions. The 1929 recession is probably the first measured world recession in that respect. Prior to that crisis, world trade was not mature enough to make a meaningful contribution to turning local growth into imported recession. But all of that now seems to be the economics of the previous century as world trade is less and less perceived as an economic boon, but as a political plague that we need to contain. Over the 2016-2019 period, voices started rising across developed economies, condemning global trade that was becoming increasingly unfair. Indeed, the dice are rigged: Ricardo’s idea of free, specialised trade works only when markets are “organised and free”. When Europe or the US start subsidising some of their industries or when China maintains a limited number of laws around its labour market, the reality departs from the theory and so do the benefits of the theory. Consequently, several anti-establishment parties started raising concerns regarding the countries that seemed to pose the biggest threat to their local job market, the primary political concern. This is, strictly speaking, a poor idea for two reasons. First, modern nations grew via the process of “creative destruction”, a term coined by economist J.A. Schumpeter. Shortly after the Second World War, the European workforce was primarily employed in the agricultural sector. Today, this percentage has dropped to under 10% yet, the sector’s production is significantly higher than what it was back then. This process takes time, but sheltering the least productive sectors of the economy has never proved successful in the past and Brazil payed a hard price for it. Second is a simple lesson from game theory: all countries have an interest in fair and free world trade as each country cannot be excellent at producing all that it consumes. By specialising and trading, each country can either reach a wider set of products or products of a higher quality. But this comes from fair play and, even though this equilibrium is the best for all, it also requires collaboration.“Buy Me a Boat” – Chris Janson, 2015

What’s Next?

Specialisation is the key

That ship has sailed

The issue is that it only takes one country to try to rig the game to its advantage to ruin this fragile equilibrium: as soon as one player tries to get more than what it can get from a collaborative situation, the rest of the players will adopt the same behavior. In game theory, this is called the “prisoner’s dilemma”: we all have a mutual interest for collaboration, but also a temptation to try to get more than the others, hoping that it will go unnoticed. Yet, once noticed, the rest of the players will retaliate by steering the situation in their interests, creating an even less optimal situation. That is exactly what is happening currently: China’s issues with intellectual property and the US’s efforts to protect its sectors threatened by international competition are two simple examples of this. Historically, world growth has evolved in a very connected way to world trade: higher growth across open economies led to stronger world trade while higher trade helped to generate growth in return. The interconnectedness of these two phenomena explains the concerns across all major economic organisations such as the World Economic Forum. In 1929, the multiple rounds of retaliation of countries raising taxes on imports was a principal driver of the recession. In our view, world trade is a real risk for markets, given the natural ties between earnings and growth. One more cloud on the horizon.Poker face

Chris Janson, 2015

Our medium-term views remain cautious, and we are pairing an overweight in government bonds with an underweight in high yield corporate credit. We are also complementing our equity exposure with options to protect the portfolio in the case of equity drawdowns. Last week, the Uni-Global – Cross Asset Navigator fund was up 0.12% versus 0.10% for the MSCI AC World Index and 0.06% for the Barclays Global Aggregate (USD hedged). Year to date, Uni-Global – Cross Asset Navigator has returned 5.01% versus 15.19% for the MSCI AC World index, while the Barclays Global Aggregate (USD hedged) index is up 2.71%.Strategy Behaviour

Performance Review

Unigestion Nowcasting

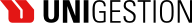

World Growth Nowcaster

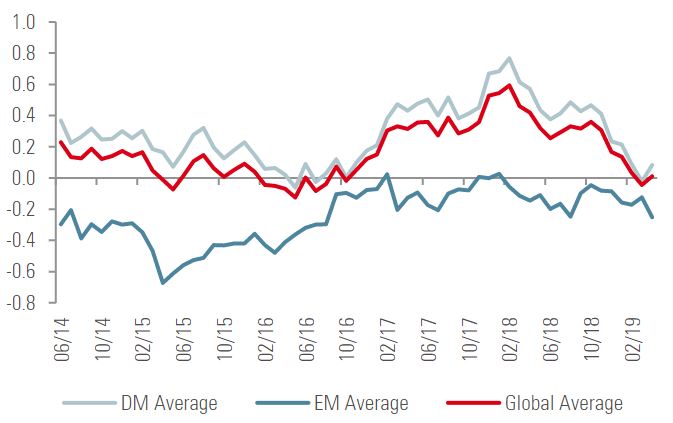

World Inflation Nowcaster

Market Stress Nowcaster

Weekly Change

- Our world Growth Nowcaster marginally increased over the week, mainly as US macro data delivered a better message. Chinese data started to deteriorate.

- Our world Inflation Nowcaster decreased again this week across most of the economies that we monitor, a continuation of a trend that started in January.

- Market stress decreased over the week, driven by lower volatility and spreads.

Sources: Unigestion. Bloomberg, as of 23 April 2019.

Past performance is no guide to the future, the value of investments can fall as well as rise, there is no guarantee that your initial investment will be returned. IMPORTANT INFORMATION Past performance is no guide to the future, the value of investments can fall as well as rise, there is no guarantee that your initial investment will be returned. This document has been prepared for your information only and must not be distributed, published, reproduced or disclosed by recipients to any other person. This is a promotional statement of our investment philosophy and services only in relation to the subject matter of this presentation. It constitutes neither investment advice nor recommendation. This document represents no offer, solicitation or suggestion of suitability to subscribe in the investment vehicles it refers to. Please contact your professional adviser/consultant before making an investment decision. Where possible we aim to disclose the material risks pertinent to this document, and as such these should be noted on the individual document pages. A complete list of all the applicable risks can be found in the Fund prospectus. Some of the investment strategies described or alluded to herein may be construed as high risk and not readily realisable investments, which may experience substantial and sudden losses including total loss of investment. These are not suitable for all types of investors. To the extent that this report contains statements about the future, such statements are forward-looking and subject to a number of risks and uncertainties, including, but not limited to, the impact of competitive products, market acceptance risks and other risks. As such, forward looking statements should not be relied upon for future returns. Data and graphical information herein are for information only and may have been derived from third party sources. Unigestion takes reasonable steps to verify, but does not guarantee, the accuracy and completeness of this information. As a result, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made by Unigestion in this respect and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. It should only be considered current as of the date of publication without regard to the date on which you may access the information. Rates of exchange may cause the value of investments to go up or down. An investment with Unigestion, like all investments, contains risks, including total loss for the investor. Uni-Global – Cross Asset Navigator is a compartment of the Luxembourg Uni-Global SICAV Part I, UCITS IV compliant. This compartment is currently authorised for distribution in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, UK, Sweden, Switzerland. In Italy, this compartment can be offered only to qualified investors within the meaning of art.100 D. Leg. 58/1998. Its shares may not be offered or distributed in any country where such offer or distribution would be prohibited by law. All investors must obtain and carefully read the prospectus which contains additional information needed to evaluate the potential investment and provides important disclosures regarding risks, fees and expenses. Unless otherwise stated performance is shown net of fees in USD and does not include the commission and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares. This document has been issued by Unigestion UK, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority. Unigestion SA authorised and regulated by the Swiss FINMA. Unigestion Asset Management (France) S.A. authorised and regulated by the French Autorité des Marchés Financiers. Unigestion Asia Pte Limited autorised and regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Performance source: Unigestion, Bloomberg, Morningstar. Performance is shown on an annualised basis unless otherwise stated and is based on Uni Global – Cross Asset Navigator RA-USD net of fees with data from 15.12.2014 to 23.04.2019.Navigator Fund Performance

Performance, net of fees

2018

2017

2016

2015

Navigator (inception 15.12.2014)

-3.6%

10.6%

4.4%

-2.2%