“One doesn’t discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore.” This quote from French author André Gide is a good reminder that, as we begin to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis, we should consider what new lands there are to discover in financial and economic theory.

We believe that the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, has modified the functioning of financial markets for the long term. Massive interventions by central banks, designed to save the global economy from major dislocations, have impacted some of the financial concepts we have been learning and applying for decades. Investors need to revisit those concepts with fresh eyes and update them where necessary for a new era.

One fundamental pillar of finance theory that warrants review is portfolio construction. Harry Markowitz’s hugely influential Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), conceived in the 1950s, not only provided investors with a means to measure risk and diversification, but also allowed them to quantify the marginal benefit of adding new exposures in order to derive the optimal portfolio allocation. While MPT was a dramatic leap forward in financial thinking, we believe many of its foundational assumptions hold with difficulty in real life. This is especially true in the current environment, where large-scale quantitative easing has structurally modified the relationship between assets’ risk and return expectations.

In this paper, we assess the impact of the GFC and COVID-19 crisis on our understanding of risk, diversification and value, and consider the implications for portfolio construction and asset allocation. In addition, as recent events have refocused the world’s attention on ESG issues, we also discuss how asset managers’ expected fiduciary duty needs to evolve, as well as the role our industry can play in forging a more sustainable economy in the future.

A New Perspective on Risk

With the massive evolution of fiscal and monetary policy that began in 2008 and accelerated with the COVID-19 outbreak, we are facing a regime shift that alters the nature of risk itself. As government bond rates are low and central banks have acted to reduce spreads for riskier assets, the risk attached to an investment today is not a reflection of its true risk.

With the massive evolution of fiscal and monetary policy that began in 2008 and accelerated with the COVID-19 outbreak, we are facing a regime shift that alters the nature of risk itself

The Difficulty of Pricing Risk

One of the bases to price risk is to start by defining the risk-free rate, i.e. the theoretical rate of return from an investment with zero risk of financial loss. US Treasuries and government bonds from other highly rated countries are widely considered to be risk-free assets, as they are fully backed by their governments. This is true in a sense, as highly rated governments have always fully paid back their debts in nominal terms. However, what many investors miss is the fact that the purchasing power of those bonds is not guaranteed due to inflation. There are two issues with the current nature of risk: risk premia are compressed and the risk-free rate is lower and more risky.

Taking Risk is a Multi-dimensional, Active Act

Despite the well-known limitations, historical volatility is often used as shorthand for riskiness in some popular risk management models. This is the case in the MPT framework. For us, risk cannot be reduced simply to one backward-looking statistic. First, it has to be about permanent loss of capital, which is the true risk investors face. Second, it should be measured using a multi-dimensional approach that is linked to the current environment. The COVID-19 crisis is a perfect example of that, as investors were faced with new risk metrics to assess, such as the contagion rate of the pandemic and the potential duration and impact of lockdowns on the economy.

The very expression ‘risk premium’ suggests that taking risk generally accompanies returns. However, given the multi-dimensional nature of risk, we are convinced that risk management needs to be active. It requires a deep understanding of which risks are worth pursuing and which to avoid, as well as a dynamic approach in order to adapt quickly to changing market conditions.

Given the multi-dimensional nature of risk, we are convinced that risk management needs to be active

At Unigestion, we take a 360-degree risk perspective that looks beyond traditional measures, seeking to model, analyse and map the broadest possible spectrum of risks to help us anticipate future risks early. By focusing on different aspects of risk, we are less dependent on individual measures, enabling us to achieve a more robust risk allocation.

We believe this multi-dimensional approach will be essential to navigate a number of key risks that are mounting today. These include:

1. Credit Risk

While the present crisis is not caused by debt, the economic side effects of global lockdowns are likely to significantly increase credit risk going forward. Although short-term risk is managed, long-term credit risk will rise.

Central banks buying credit have reduced the perceived tail risk of credit. Their action, together with fiscal policies put in place by countries, will be an incredibly powerful tool for our economy. In the months ahead, such interventions will enable many individuals, companies and local governments to survive an economic decline that would otherwise be devastating. However, credit risks are growing in the economy due to credit misallocation and increased solvency risks. We are experiencing a situation in which many countries and companies, already highly leveraged, are taking on more debt.

In recent decades, investors have favoured companies that rely on financial engineering, such as increasing debt or implementing stock buybacks, to maximise their profitability. However, this recent crisis has shown that prioritising purely profitability creates fragility. In these uncertain times, identifying resilient companies will be key. Fundamental ratios that have been forgotten over the past decade, such as debt-to-equity, interest coverage and cashflow robustness, will move centre stage.

2. Government Intervention/Financial Repression Risk

The huge amount of government debt accrued during the current crisis ultimately will have to be repaid, be it through higher taxes, inflation or other financial repression measures, meaning that longer-term tail risks have increased. In emerging markets, government regulations, such as de facto caps on profits for utilities, have been quite common, but we could now see similar situations arising in developed countries across various industries, such as utilities, automobiles or airlines. As an example, the French government’s EUR 15 billion support package for the aerospace industry will have some strings attached on how companies run their business models. This new type of risk, which econometric models can only assess retrospectively, highlights the importance of combining systematic analysis with forward-looking fundamental research. Understanding government-related risks also has implications for asset allocation and may challenge some traditional models that favour large weightings in the US, for example.

3. Liquidity Risk

Liquidity risk is volatile, but generally strikes at the worst of times, so it is better be prepared for it. March and April showed the eruption of an unprecedented liquidity crisis in financial markets, when even government bonds experienced spread increases never seen before. This shows that liquidity is one of the most critical, but least quantified risk dimensions in portfolio construction.

Traditional portfolio construction techniques, including mean-variance optimisation or risk parity, focus heavily on return variability and drawdowns, but often treat liquidity risk as a secondary consideration. At Unigestion, we believe that liquidity risk should be a direct input in portfolio construction and we include it on an ex-ante basis in our proprietary Expected Shortfall model to assess risk.

4. ESG Risk

ESG risk is an increasingly important consideration for investors. Well before the current crisis materialised, we were living in an era of rising inequalities, growing awareness of damaging corporate governance failures and increasing urgency around the climate change challenge. However, we believe the COVID-19 outbreak has brought us to a tipping point and we are witnessing a change of regime where society will no longer tolerate these imbalances and fragilities.

Companies that do not pursue sustainable practices on a day-to-day basis create operational and reputational risks within their businesses and to their business model. Meanwhile, new regulation can make or break entire industries. Whether it is about increasing tax, cutting emissions in polluting industries or regulating digital companies, it can have a direct impact on the companies in which we invest. Anticipating and avoiding these risks will be key.

At Unigestion, we approach ESG in the same way as all investment risk, carefully assessing the potential impacts through a combination of systematic and discretionary top-down and bottom-up decisions. We expect ESG integration to be beneficial for long-term risk and therefore long-term risk-adjusted returns, although we do not support a positive or negative relationship between ESG criteria and performance in theory.

Does Diversification Still Work?

A second key concept to revisit is diversification, which has been the cornerstone of investing since Markowitz published his seminal article, Portfolio Selection, in 1952. The benefits of diversification across assets have been challenged over the last 10 years, when few strategies would have beaten a simple 60/40 portfolio comprising US equities and government bonds.

The benefits of diversification across assets have been challenged over the last 10 years, when few strategies would have beaten a simple 60/40 portfolio comprising US equities and government bonds

The magic behind diversification – and one of the reasons it is often cited as the only “free lunch” available in investing – is that a portfolio of assets will always have a risk level less than, or equal to, the riskiest asset within the portfolio. The theory has its shortcomings, however, and unfortunately, diversification can fail dramatically during market crises, just when investors need it most.

During the COVID-19 market crisis, there has been an unprecedented rise in correlation between different asset classes. Certain assets have fared better than others, but the list of winners during the initial sell-off was very short: US Treasuries, German government bonds, Swiss francs and gold. Furthermore, the size of the gains from those assets were relatively small, ranging from +0.7% to +6%, compared to a fall of more than 30% for equity markets (over the period 20.2.20 – 30.03.20). Needless to say, bonds did not offer the level of protection they have in the past, in part due to their low level of yield.

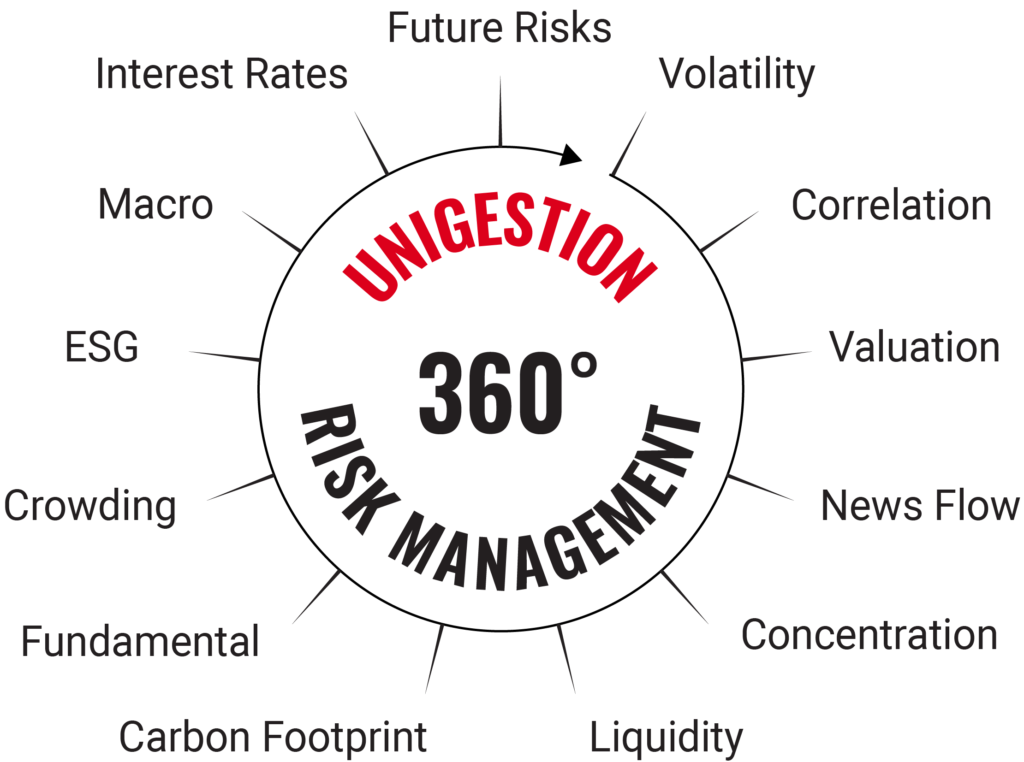

Figure 1: Average Cross-asset Correlation Has Risen in Recent Decades

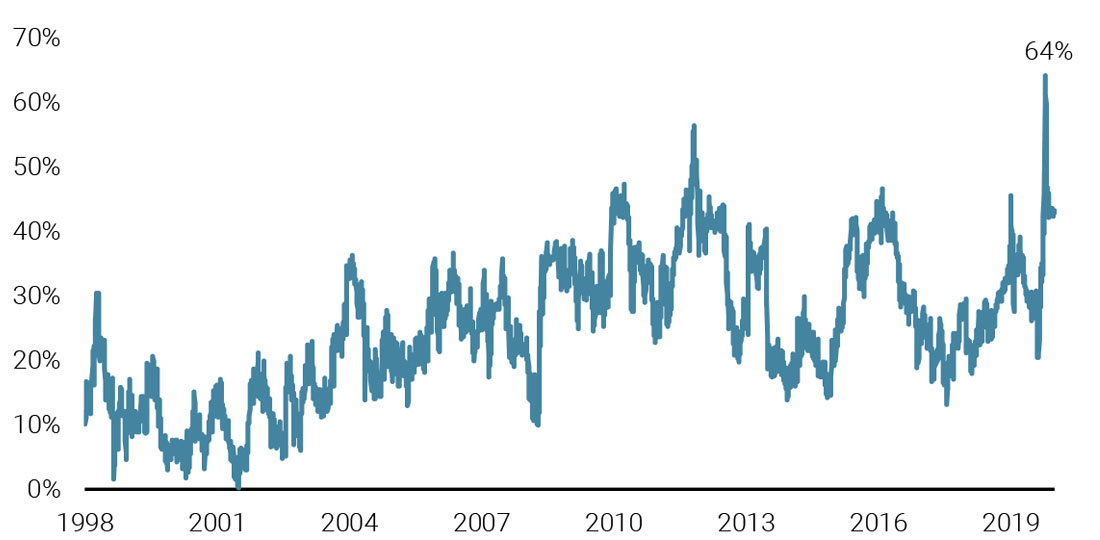

Diversification across global equity markets has not paid off during the recent crisis either. Correlation between global stock indices generally decreased following the GFC but spiked again with the COVID-19 outbreak. Structural changes, including significant growth in passive investment strategies, high frequency trading and factor investing, have amplified those behaviours during the crisis.

Figure 2: Global Equity Market Correlation Spiked During the COVID-19 Crisis

At Unigestion, we continue to believe in diversification and consider its recent failure to be a cyclical phenomenon, notably due to the unprecedented central bank action, which led to a concentration in most traditional assets. As was the case after the GFC, we expect correlation and dispersion to become more favourable to diversification.

Generally, diversification does not tend to pay off during the first leg of a significant market correction. Dispersion usually remains low initially as systematic de-risking negatively affects all stocks indiscriminately, but we expect more dispersion to materialise in the coming months.

Furthermore, prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, economic growth had been the key driver of market performance for more than a decade. This should change as we move into a more volatile economic environment that should be discriminatory in terms of countries, sectors and styles. Different risk premia should start to respond differently again. However, the rise in correlation, together with heightened market volatility, suggest a reappraisal is required when seeking diversification.

Enhancing Diversification Across Macro Regimes

We believe that diversifying across asset classes is too simplistic since the underlying risk drivers can be the same. Instead, we believe a portfolio should be diversified across macroeconomic regimes and invest into assets that respond differently to these macro conditions.

[/col-full][/row]

We believe that diversifying across asset classes is too simplistic. Instead, a portfolio should be diversified across macroeconomic regimes and invest into assets that respond differently to these macro conditions

Our research shows that the macroeconomic environment typically falls into one of four regimes – steady growth, recession, inflation shock and market stress – which tend to occur with a similar frequency across all regions and periods. We believe it is important to ensure portfolio risk allocation is aligned with the long-term probabilities for the various regimes.

It is also essential to adapt portfolio positioning as market conditions change. At Unigestion, we use our proprietary Nowcaster indicators to monitor the risk of recession, inflation and market stress in real time. The output from these sophisticated tools allows us to dynamically adjust our portfolios to the prevailing environment.

Today, we are at spectacular juncture in terms of the macro and market cycle. Our economy is facing a deep recession due to an exogenous shock and the efforts of central banks and governments will have a huge influence on the return to growth trajectory. However, this potentially creates a risk of inflation. Furthermore, while markets stabilised in April thanks, here again, to central bank intervention, we believe that they are vulnerable to other stress events. In our view, a robust portfolio should have some exposure to all these outcomes, as we will discuss in more detail later.

What Does Value Mean?

Today, we are in new territory where ‘All-in Easing’ has created unlimited demand for financial assets, raising the question: what does value mean? The scale and scope of current monetary policy has been so large and broad that it has potentially destroyed the historical relationship between fundamentals and market pricing. As per Oscar Wilde’s quote in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, “Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

We are witnessing some valuation distortions across asset classes because 1) the risk-free rate is distorted and 2) we have a buyer of last resort for a large spectrum of risky assets. Government bond yields in the US and other large economies reflect the return investors can expect to earn without taking risk, which serves as the foundation on which you build every asset’s expected return. If government bond yields are distorted, so too are the prices of stocks, corporate bonds and everything else. Furthermore, central banks extending their programmes beyond investing in government bonds reinforces the compression of risk premia embedded in any risky asset.

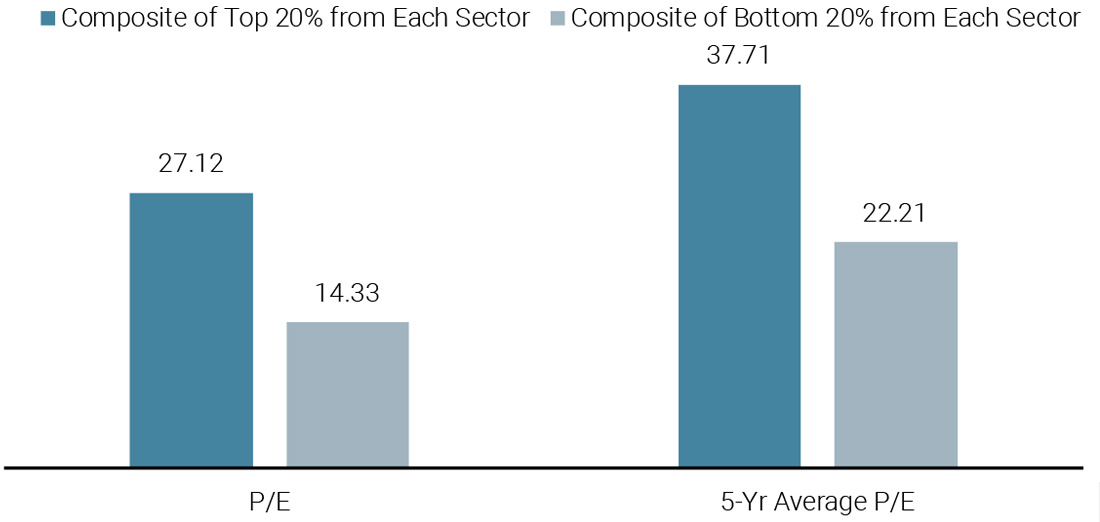

There are also valuation distortions within asset classes. The dispersion between equity valuations in particular is massive. As of the end of April, the top 20% of stocks from each S&P 500 sector combined are trading at 27 times their earnings, compared to a multiple of 14 for the bottom 20% of stocks within the same sectors.

Figure 3: Dispersion Between P/E Valuations in the S&P 500

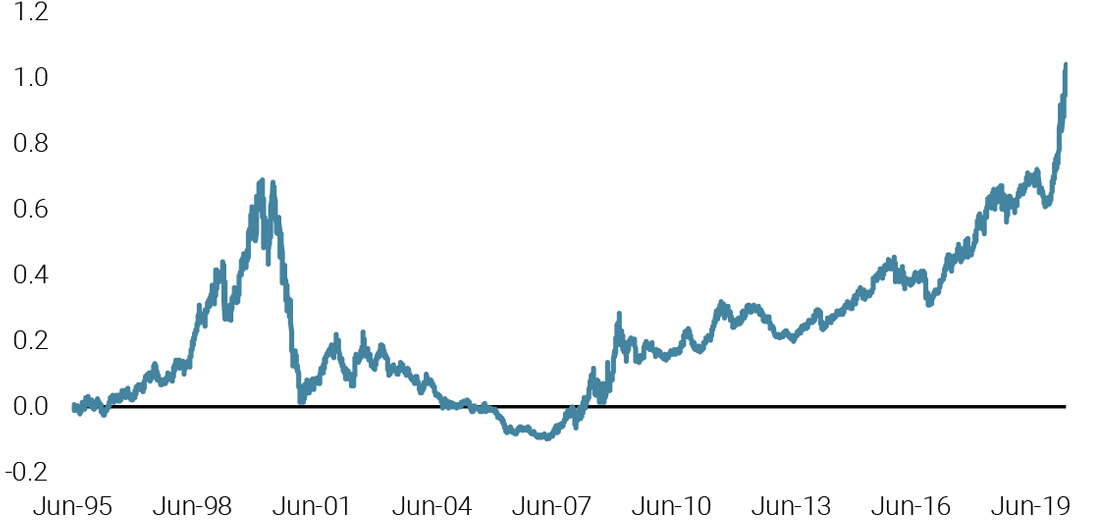

These distortions have raised questions around whether value investing has run its course. Value style has experienced an extraordinary period of underperformance relative to growth investing, spanning more than 13 years. Value has become so cheap versus growth that its current valuation is in the 97th percentile of its historical distribution.

Value style has experienced an extraordinary period of underperformance relative to growth investing, spanning more than 13 years

Figure 4: Growth vs Value Spread

Value investing has deep roots and a long history. Graham and Dodd laid out its main principles in their 1934 classic book, Security Analysis. It was then heavily influenced by the work of professors Fama and French, who proposed a three-factor model, which extends the classic Capital Asset Pricing Model with the size and value factor. However, today there is mounting concern that the value premium may have disappeared permanently. A number of narratives have been offered to explain why ‘this time is different’ and why the value factor’s poor relative performance may be the ‘new normal’. One such theory is that the value definition has become obsolete.

It is true that value can no longer be defined solely as book value, as proposed by the Fama-French model, but for every definition of value we examine in measuring relative cheapness – price-to-book, price-to-earnings, price-to-sales and price-to-dividends – it has underperformed growth since 2008. Furthermore, the definition of ‘cheap’ is no longer limited to industrial companies, cyclical stocks or financials. Looking at the one-year return for the value factor by sector (as at end May), there were no sectors with a positive value spread in Europe and only one in the US, namely Healthcare.

We believe that there is no reason why the value premium should have disappeared. Such a lost decade is not unprecedented in history and variations are still well within the range that may be expected statistically. Indeed, value performance in the 2010s was remarkably similar to the 1990s, which is perhaps unsurprising since both these decades also saw double-digit excess returns for the equity market.

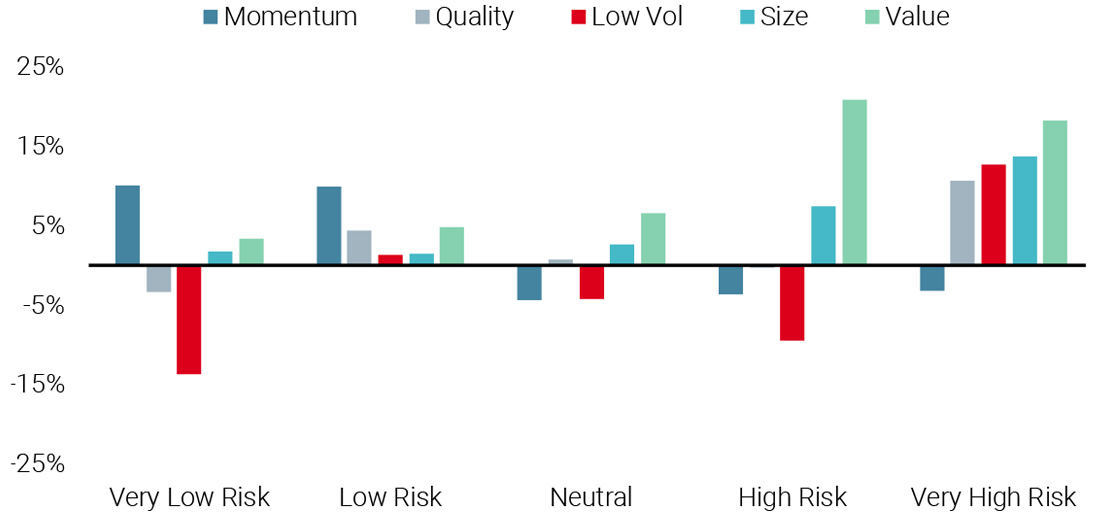

Factor premia, including value, still exist and should deliver long-term performance. However, their performance in the short term can be quite cyclical and extreme. For that reason, we prefer a diversified factor exposure in our risk-based equity strategy, rather than favouring any one factor. We then use our proprietary Nowcaster indictors to adapt our factor exposures to the prevailing market environment. As illustrated in Figure 5, which shows factor performance at different levels of recession risk over the past 20 years, some factors tend to perform better than others in a recessionary environment.

Figure 5: Factor Performance at Different Levels of Recession Risk

It is not surprising that the dispersion of valuations is so extreme. The dispersion of earnings estimates for S&P 500 companies is also at its widest, as a record number of firms have suspended their guidance. The number of US blue-chip companies offering full-year guidance with their first-quarter earnings has halved in 2020. In a period where earnings are so difficult to estimate, even for companies themselves, short-term valuations become less meaningful, especially so when using systematic measures. There is a need for more holistic fundamental analysis to review the long-term value proposition of a company to be able to derive its long-term valuation.

Portfolio Positioning in a Post-Crisis World

The challenge for investors today is how to gain exposure to future growth and central bank stimulus while also protecting their portfolios against an imminent recession and potential market stress events. We believe this can be achieved in several ways:

The challenge for investors today is how to gain exposure to future growth and central bank stimulus while also protecting their portfolios against an imminent recession and potential market stress events

1. Invest Selectively in Equities

This unprecedented liquidity boom, combined with a significant reduction in the discount rate, is a positive catalyst for equity markets. Furthermore, with rates likely to be lower for longer, we expect the risk premia associated with equities to be compressed over time. Looking at the relative value between stocks and bonds, the chief risk for stocks would be a further plunge in earnings, coupled with a rise in defaults. However, even if current earnings estimates are too high, stocks still look cheap relative to the bond market as their discount rate has decreased so much.

These factors helped major equity indices to recover from their end-March lows at an unprecedented pace and may now create more opportunities for active managers to exploit. We favour a selective approach, especially within growth-oriented assets. Among our key dynamic views is a preference for ‘defensive’ equities, which show resilience in their activities, cashflow and balance sheets. We believe these firms are well suited to weather the current storm and thrive when the economy recovers. The prospect of challenging earnings in 2020 will test investors’ tenacity, but if balance sheets can cope, then the value of a company is still the value of the long-term free cash flows into eternity.

However, it is important to be mindful of investing in equity indices due to their momentum characteristics and bias towards stocks that have performed well. Many indices are heavily concentrated in certain sectors or companies, perhaps most notably the S&P 500, where technology firms account for 26%, with the top five stocks (Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Alphabet) comprising 21% of the index (as at end May).

2. Invest in Private Equity to Diversify Growth Exposure

Another important consideration is that listed equity markets are not the sole providers of growth capital. The number of public companies has diminished over the past decade, thanks to increased M&A activity and fewer IPOs. In the US, for example, the number of listed companies has declined by around 40% from its height in 1996. This shrinking universe for public equity, coupled with increased financing opportunities in the private markets, means investors need to turn to private equity to gain a diversified exposure to economic growth.

With the number of listed companies shrinking, investors may need to turn to private equity to gain a diversified exposure to economic growth

The changing ownership of public equity markets is also a reason for this development. There is a different alignment model between company management teams and investors compared to 20 or 30 years ago. In the public space, corporate management teams may not have as much latitude to restructure their business models and, if they miss analysts’ expectations for the quarter, they might draw the attention of short-termist investors. That is why many companies prefer to remain private for longer. Company management teams are now more aligned to private equity sponsors in terms of five- to seven-year time horizons than the public markets.

Investing in private equity when facing a recession requires a selective approach, but there are still significant opportunities. Looking back to 2007/08, some of the best vintages of the last 15 years emerged from the crisis. Private equity investors were able to benefit from lower entry valuations in the years immediately following the GFC, while the eventual economic recovery from 2009 onwards provided a useful tailwind to all companies. At Unigestion, we believe that the next one to two years will provide similar conditions for investors.

However, we prefer portfolios of small and mid-market companies, as these companies show better resilience than large and mega-cap firms. Indeed, small and mid-market companies tend to have lower leverage and often operate in niche sectors or in those that are less sensitive to economic vicissitudes. Given their lower leverage and generally stronger balance sheets, it is also easier for them to absorb a temporary reduction in EBITDA and an increase in debtors and/or inventory.

3. Balance the Competing Forces of Deflation and Inflation

Investors should prepare for a future battle between deflationary and inflationary forces and balance their portfolios accordingly. The impact of COVID-19 will likely be deflationary at first, due to the demand shock and low growth. However, even if inflation seems off the radar for now, the seeds of higher inflation may already have been sown. The direct monetisation of budget deficits, a retreat from global trade and a rebalancing of social and political policies in favour of labour are all inflationary forces.

We believe that an allocation to equities and private equity, as mentioned above, can provide a good long-term hedge for inflation, as it will provide real exposure to the economy where inflation will be priced in.

4. Protect Against Market Stress Episodes

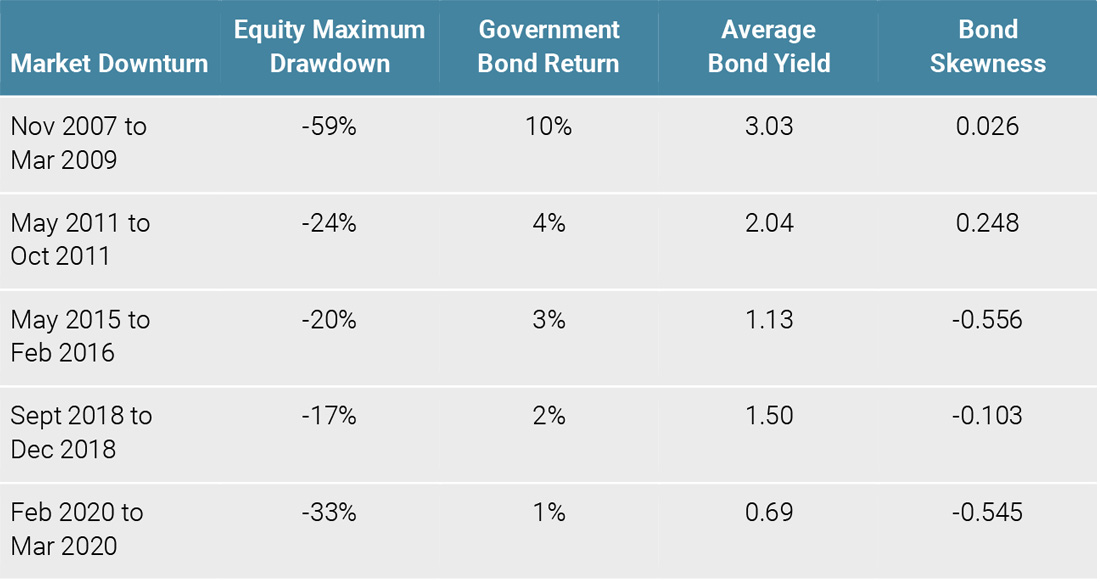

With markets still vulnerable to episodes of market stress, it is important to build in some downside protection. It is widely assumed that government bonds are inherently ‘safe’ investments and that they provide defensive risk diversification benefits when included in an overall asset allocation. During previous slowdowns, government bonds have acted as a powerful diversifier, but much less so during the COVID-19-led market correction.

Figure 6: Bond Hedging Capabilities Continue to Decline

Bond hedging capabilities are now more limited, as yields are already at very low levels. Low bond yields mean small yield cushions, which directly reduces their defensive benefits. They also make the forward-looking risk-return profile of bonds unfavourably asymmetric.

We believe investors need to broaden their toolkit to protect against market corrections. Equity derivatives can help investors to protect their equity allocations against market downturns without having to significantly increase their exposure to cash.

We believe investors need to look beyond government bonds to protect their portfolios against market corrections

Using a combination of both explicit and implicit hedging strategies helps to reduce the cost of carry while maintaining a high probability that the protection will be effective when needed. Explicit hedging strategies consist of selecting an attractive portfolio of options, while implicit hedging strategies rely on statistical properties, such as a negative correlation, trend-following or mean reversion.

Moving Towards a More Sustainable Future

As asset managers, our fiduciary duty to our clients is to deliver long-term sustainable returns. This means investing responsibly in companies, industries and projects where there is an objective to create a sustainable future for society, as this kind of investment should generate better long-term risk-adjusted performance going forward for our investors.

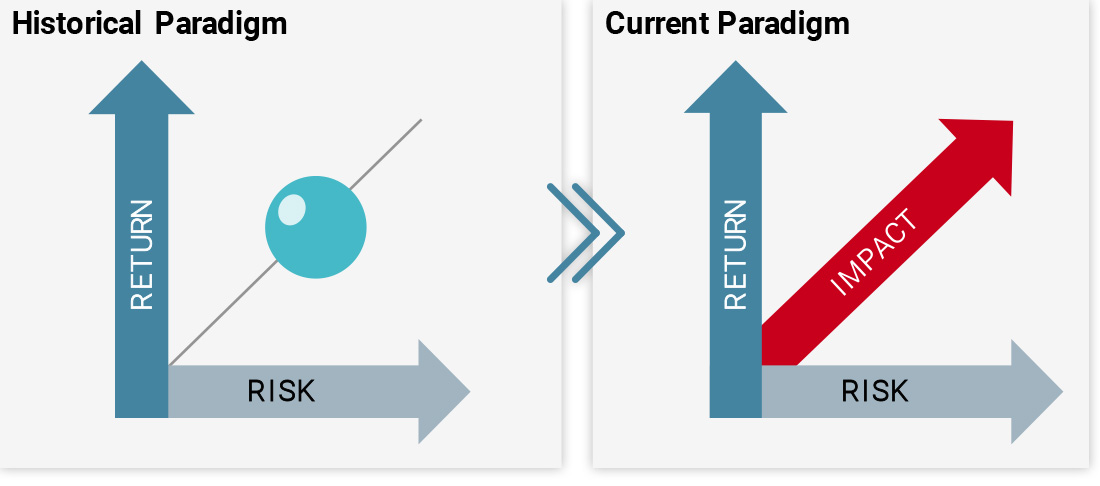

Enlarging the MPT Framework

Returning to Markowitz’s MPT framework, we believe a two-dimensional risk and return model is no longer sufficient to construct portfolios to meet this sustainability objective. Instead, we should move towards a three-dimensional model where we consider not only the risk and potential return of an investment on our allocation, but also its ESG impact.

Figure 7: Moving from Two Dimensions to Three

Our analysis shows that adding both bottom-up and top-down ESG restrictions into the portfolio construction process under realistic transaction costs and liquidity assumptions does not change the efficiency of the portfolio in an economically significant way. On the contrary, there is evidence of a slight improvement of the risk-adjusted performance and downside protection with additional ESG risk considerations. This means that investors can achieve their objectives in terms of both risk and performance, while at the same time addressing their ESG preferences.

Towards a More Purpose-Driven Capitalism

Institutional investors and asset managers are moving away from the shareholder value maximisation philosophy, as famously espoused by Nobel economics laureate Milton Friedman in 1970. Instead, they are increasingly recognising that corporations have responsibilities towards all stakeholders affected by their businesses. Asset owners are devoting more resources to invest and engage in companies, projects or countries that take into account these interdependencies, as we have seen with the PRI, Climate Action 100 or the UK Stewardship Code initiatives.

Friedman’s more extreme form of shareholder capitalism, which became popular during the 1980s, advocated that the role of business was to enhance returns for shareholders and that any consideration of ESG criteria would be in direct conflict with the duties of company management. However, classical economic theory is not well equipped to describe the interdependence of finance, business, the economy and society on broader terms. Neither does it account for multi-generational economic transfers, in which current generations are willing to forgo consumption with no recompense in order that future generations can benefit. Today, many would argue that Friedman’s analysis has proved to be harmful not only for wider society, but also for shareholders themselves.

Regaining Trust in the Financial Sector

There has been considerable scepticism among the public about the role of the financial sector since the GFC. Regaining system stability and public trust has been a core challenge. The Edelman Trust study, which is published annually, shows that finance remains one of the least trusted sectors in society, although its scores have improved in recent years.

The global economy is going to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis in desperate need of growth. Asset managers have an important role to play not just in terms of providing returns for their clients, but also in creating real value for society. Unlike banks, which use short-term funding to allocate capital, asset managers use the long-term funding provided by institutional investors and so represent a crucial link between investors and the financing needs of the real economy. However, the end goal should not be growth at any cost, but rather sustainable economic expansion that minimises the risk of another major crisis. Whereas in previous decades, the financial system was there to provide the flow of capital necessary for the economy to grow, this goal was lost in the GFC. Our aim now must be to ensure the financial system is once more the means rather than the end in itself.

The global economy will emerge from the COVID-19 crisis in desperate need of growth. Asset managers have an important role to play not just in terms of providing returns for their clients, but also in creating real value for society

Delivering for Clients in a Changing Environment

Paul Samuelson, winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics, responded to criticism that he had changed his view on the acceptable level of inflation by saying “Well when events change, I change my mind. What do you do?” We can admire the humility necessary to answer in this way all the more when coming from a Nobel laureate. We can also learn from it when our environment is changing, as has been the case lately.

The current crisis will likely have far-reaching impacts on our notion of society, the economic landscape and the functioning of financial markets. As such, we will need to rethink what it means for our investment approaches and for the needs of our clients. We would argue that most of these changes started following the GFC and have been amplified by the current crisis.

As asset managers, we need to have a certain humility to accept the fact that we do not know anything for sure. Even less so today, when the global health, economic and financial market situation depends on many parameters that interact with one another and that we do not control. Therefore, our views evolve through time as new information emerges.

For Unigestion, risk management is not merely a means of risk mitigation, but a means of value creation

Nevertheless, it is still possible to deliver for our clients even in uncertain times and this is what we mean by active risk management, which lies at the heart of our investment philosophy. We can never be sure of an outcome, but we can prepare for it and decide which risks we are comfortable taking and those we are not. By taking risk in a measured, informed way, we aim to deliver the performance our clients expect. For Unigestion, risk management is not merely a means of risk mitigation, but a means of value creation.

Important Information

Past performance is no guide to the future, the value of investments, and the income from them change frequently, may fall as well as rise, there is no guarantee that your initial investment will be returned. This document has been prepared for your information only and must not be distributed, published, reproduced or disclosed by recipients to any other person. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation.

This is a promotional statement of our investment philosophy and services only in relation to the subject matter of this presentation. It constitutes neither investment advice nor recommendation. This document represents no offer, solicitation or suggestion of suitability to subscribe in the investment vehicles to which it refers. Any such offer to sell or solicitation of an offer to purchase shall be made only by formal offering documents, which include, among others, a confidential offering memorandum, limited partnership agreement (if applicable), investment management agreement (if applicable), operating agreement (if applicable), and related subscription documents (if applicable). Please contact your professional adviser/consultant before making an investment decision.

Where possible we aim to disclose the material risks pertinent to this document, and as such these should be noted on the individual document pages. The views expressed in this document do not purport to be a complete description of the securities, markets and developments referred to in it. Reference to specific securities should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell. Unigestion maintains the right to delete or modify information without prior notice. Unigestion has the ability in its sole discretion to change the strategies described herein.

Investors shall conduct their own analysis of the risks (including any legal, regulatory, tax or other consequences) associated with an investment and should seek independent professional advice. Some of the investment strategies described or alluded to herein may be construed as high risk and not readily realisable investments, which may experience substantial and sudden losses including total loss of investment. These are not suitable for all types of investors.

To the extent that this report contains statements about the future, such statements are forward-looking and subject to a number of risks and uncertainties, including, but not limited to, the impact of competitive products, market acceptance risks and other risks. Actual results could differ materially from those in the forward-looking statements. As such, forward looking statements should not be relied upon for future returns. Targeted returns reflect subjective determinations by Unigestion based on a variety of factors, including, among others, internal modeling, investment strategy, prior performance of similar products (if any), volatility measures, risk tolerance and market conditions. Targeted returns are not intended to be actual performance and should not be relied upon as an indication of actual or future performance.

No separate verification has been made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information herein. Data and graphical information herein are for information only and may have been derived from third party sources. Unigestion takes reasonable steps to verify, but does not guarantee, the accuracy and completeness of information from third party sources. As a result, no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made by Unigestion in this respect and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. It should only be considered current as of the date of publication without regard to the date on which you may access the information. Rates of exchange may cause the value of investments to go up or down. An investment with Unigestion, like all investments, contains risks, including total loss for the investor.

Legal Entities Disseminating This Document

UNITED KINGDOM

This material is disseminated in the United Kingdom by Unigestion (UK) Ltd., which is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”). This information is intended only for professional clients and eligible counterparties, as defined in MiFID directive and has therefore not been adapted to retail clients.

UNITED STATES

This material is disseminated in the U.S. by Unigestion (UK) Ltd., which is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). This information is intended only for institutional clients and qualified purchasers as defined by the SEC and has therefore not been adapted to retail clients.

EUROPEAN UNION

This material is disseminated in the European Union by Unigestion Asset Management (France) SA which is authorized and regulated by the French “Autorité des Marchés Financiers” (“AMF”).

This information is intended only for professional clients and eligible counterparties, as defined in the MiFID directive and has therefore not been adapted to retail clients.

CANADA

This material is disseminated in Canada by Unigestion Asset Management (Canada) Inc. which is registered as a portfolio manager and/or exempt market dealer in nine provinces across Canada and also as an investment fund manager in Ontario, Quebec and Newfoundland & Labrador. Its principal regulator is the Ontario Securities Commission (“OSC”). This material may also be distributed by Unigestion SA which has an international advisor exemption in Quebec, Saskatchewan and Ontario. Unigestion SA’s assets are situated outside of Canada and, as such, there may be difficulty enforcing legal rights against it.

SWITZERLAND

This material is disseminated in Switzerland by Unigestion SA which is authorized and regulated by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (“FINMA”).

SINGAPORE

This material is disseminated in Singapore by Unigestion Asia Pte Ltd. which is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”).

Document issued June 2020.